On July 10, KKL-JNF’s marketing department joined a press tour organized by the KKL-JNF Spokespersons Unit to the Upper Galilee. We saw the blackened ground and burnt trees of the Biriya Forest, and smoke still rising from the ground. We spoke with KKL-JNF field professionals as well as civilian volunteers and business owners in order to gain an overall picture of what has been happening in the north since October 8, and especially since Mid-May, with the onset of the warmer, dryer seasons, in order to get a broad, in-depth picture of what is shaping up to be the biggest natural disaster to befall KKL-JNF since its founding over 122 years ago.

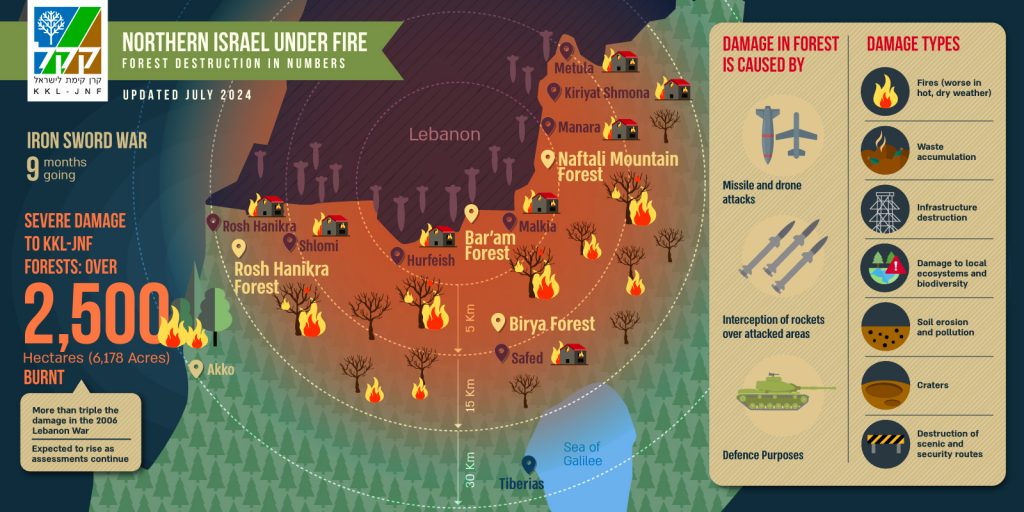

Since the outbreak of the Iron Swords War, huge swathes of KKL-JNF woodland have gone up in flames, particularly in the Upper Galilee and Golan Heights

In a “normal” year, about 60-150 hectares of forest are burnt by wildfire. This year, the number has skyrocketed to over 2,500 ha., a record for KKL-JNF forests. The damage has already reached triple that of the 2nd Lebanon War in 2006, which saw 700 ha. of woodland burnt. This grim tally is set to rise. “There are thousands of more dunams of forest right on the Lebanese border, but they are closed military zones, and we have no idea what’s happening with them,” says Shali Ben Yishai, the director of the KKL-JNF Northern Region.

Ben Yishai explains that KKL-JNF’s northern region is comprised of 4 areas: Lower Galilee-Gilboa, Western Galilee-Carmel, Hula Valley, and Upper Galilee-Golan Heights. Each area has a standing KKL-JNF firefighting array including 3 firetrucks and a team of highly trained firefighters, but their main work is maintaining the forests.7

“Now, in the Upper Galilee-Golan the formula has reversed, and we operate in a constant state of alertness and readiness since we don’t know when the next event will occur, how much it will spread, how many fire spots there will be. We are hyper focused on preventing spread and minimizing the damage. Unfortunately, we barely succeed,” Ben Yishai says.

He gives an example of an event from two weeks ago, when about 150 rockets and drones fell or were intercepted in this area, resulting in heaps of burning falling fragments falling here. “Upon arrival we see that there are suddenly 30-40 fire points, smoke everywhere, making it hard to know where to start. And at the same time another fire breaks out in a forest far from the area. I want to thank and salute my staff, who work fiercely day and night to prevent the next fire, and also to the Fire and Rescue Services who work with us closely.”

Eli Haputa, head of the Upper Galilee-Golan Heights area, elaborates on the risks involved.

“During the fall and winter period the rockets did not cause fires since the ground was saturated with water. But from around May 10 onwards, every rocket strike in a forest has a 100 percent certainty of becoming a fire point, and every interception fallout can become several fire points. In a single day there could be dozens of fire points, which even an entire array or joint effort with other forces cannot adequately fight. Upon the slopes the danger is compounded for a firefighter, who doesn’t know in which direction to flames will spread. And since the fire also burns underground there is a high chance of the flames sprouting up elsewhere a few days later. For those reasons we are in a constant state of readiness, and this past month we haven’t been able to do any routine forest maintenance at all.”

Ben Yishai notes that even the array of the entire KKL-JNF northern region is insufficient to battle fires of such intensity and frequency, which is why the organization has mobilized its entire array countrywide, with reinforcements arriving from central and southern regions. In addition, KKL-JNF teams work closely with the Israel Fire and Rescue Services, the IDF, the Nature and Parks Authority, and local civilian response teams.

Eitan Lebel, an Amuka resident who has volunteered on his civilian response team for decades, notes the difference between firefighting now and in 2006 during the Second Lebanon War, in which they dealt with falling Katyusha rockets. “This time the weapons are bigger, heavier and more destructive, and also the Iron Dome interceptions create a lot of fragments on impact.”

The previous generation of foresters, such Artur Yankelov, a veteran KKL-JNF forester of 28 years, have witnessed their life’s work go up in flames. As a long-time resident of this region, he recalls living through the 2nd Lebanon War. “Back in 2006, we thought that this would be the last war,” he says sadly. “Since then, we have raised a forest [rehabilitated from the burnt one], and I raised a son who grew alongside it. This month he is about to be drafted, and we find ourselves returning to the same situation as then…we hope that in the end our work will remain for the next generation.”

The ecological impact of the fires is immense. The forest is a complete habitat to a wide range of wildlife, from insects to reptiles through to birds and mammals big and small. The fires have had a devastating impact on biodiversity. “Wildfires are a part of nature”, explains Yaron Charka, KKL-JNF’s Chief Ornithologist. “When they occur [in their natural time] during the fall, birds have evolved over millions of years to cope by simply spreading their wings and flying. But there are fires that occur in a very unnatural way, as with the current war, in the tail end of spring, the height of the nesting season.” Bird species that have been affected include the Eurasian hobby, which nests in Biriya Forest and lays eggs relatively late in the season, as well as the Snake eagle, the Eurasian sparrowhawk, and the Tawny owl. “There is no doubt that the fires have destroyed chicks and eggs,” says Charka, “and we have lost an entire generation of Eurasian sparrowhawks and Tawny owls.”

The forest ecosystem expands far beyond the flora and fauna to incorporate the human and economic systems as well. Cattle growers, for example, rely heavily on the forest floors to graze their flocks. The forests in turn benefit since their grazing reduces the amount of flammable undergrowth and enriches the soil.

Ilan Tibi, who manages KKL-JNF’s Grazing Unit countrywide, says that the loss of 13,000 ha. of open space, including the 2,000 ha. of KKL-JNF forest, has dealt an enormous blow to cattle growers, with their flocks unable to graze, and fences and facilities damaged, causing cattle to wander off and get lost. “We at KKL-JNF and the Agricultural Ministry have been helping them, mainly with equipment such as mobile pens in order to consolidate the wandering flocks, and troughs for water”, says Tibi. “We do our best to assist them since in the end grazers are part of our fire prevention efforts in routine times.”

The cattle growers we spoke with say that the damage they’ve sustained has been in the tens of millions of shekels, and the government has yet to provide assistance. “The flocks that are our livelihood are sustained by what grows on the ground,” says Amir Bider, a cattle grower from Tzfat. “I had 600 ha. worth of grazing ground available to me that have been completely burnt, which means that I now have to purchase feed at a cost of hundreds of thousands of shekels. Not everyone has that kind of money available. I’m currently living off savings and assistance from my family and other good people.”

And this is before mentioning the loss of cattle that fled or drowned in swamps. “The only ones who have helped us have been KKL-JNF,” says Bider. “For example, three of my cows wandered into a quarry in search of water and got stuck in the mud. KKL-JNF brought a truck and a crane, and we managed to extract two of them alive. To this day I have cows wandering around Kiryat Shmona and the Ramim Ridge [of the Naftali Mountain Range]. In the Ramim Ridge I have 240 heads of cattle, some of them dead and others lost; I cannot retrieve them due to the entire area being a closed military zone, and I have no idea what’s happened to them.”

Cattle grower Lior Haber, who lost 1,400 ha. of grazing grounds due to fires, expands on what such loss entails. “With 240 heads of cattle, you’re talking about a loss of 8,000 NIS multiplied by 240. Even before the war it wasn’t easy to make a living, what with agricultural theft and robbery. My grazing area has been burnt twice due to missiles falling. I immediately called KKL-JNF’s 102 hotline, and their firefighting team together with that of the Nature and Parks Authority helped me put out the flames. Two days later Ilan called and asked me about the damage, and I mentioned that my cattle bridges burnt, and my fences burst open. Soon after a KKL-JNF clerk called to notify me that there was replacement equipment waiting for me to pick up so that I could fix the fence.”

In areas where cattle graze, there is no fire spread; grazing not only protects the forests but also ensures that the flames don’t reach the nearby yishuvim. Furthermore, grazing also enriches the soil. KKL-JNF Northern Region Director Shali Ben Yishai mentions research done in which they removed grazing cattle from flowering areas for a period of 3-4 years. The resulting vegetation cover cut off the geophytes, causing the wildflowers to disappear and reducing biodiversity. In fact, grazing has long played a crucial role in managing Mediterranean ecosystems.

Eitan Lebel, who resides in Amuka, established the Bat-Yaar Farm in 1985 as a tourist attraction offering horse riding, jeeping, and group events in the heart of the forest. The rustic trestle tables in the lovely outdoor dining area have become a repository for coils of fire hoses and firefighting equipment. “It is the most central place to keep them since we don’t know whether the next fire will break out from the north, south, east or west,” he says. Lebel’s business, which before the war had 106 employees, has been shut since October 8.

Lebel jokes that the only ones enjoying the situation are the horses, who have been put out to pasture. “We are now in July, the height of the tourist season,” he says. “Normally on a day like this we’d be hosting 300-400 people, but as you can see the place is empty.”

After October 7, the local community organized themselves into a civilian response unit, which Eitan Lebel heads. After the initial training and equipping stage, and the onset of the warm weather, Lebel says, his team pivoted to becoming a volunteer firefighting squad.

“These guys go out once or twice a day to deal with a fire outbreak. Our advantage of being located in the middle of a forest is the rate of response. When a fire is still small, it’s easier to gain control, you can tackle it with a fire extinguisher or jerry can. But when it starts to spread and climb the trees, only fire extinguishing planes help. We have a great team; as soon as we hear an explosion or interception, and it sounds close enough, patrols immediately go out in all 4 directions in order to locate the fire. As soon as we locate it, we sound the alarm; the firefighting forces closest and most available to us most times are those of KKL-JNF, who know the forest best and how to fight fires. Then they take over. We return in order to put out recurring fires. The most recent critical fire we stopped had reached about 40 meters from here,” says Lebel. “The cooperation with KKL-JNF is fantastic.”

Rami Zaretzki, in charge at KKL-JNF of protecting forests from fires, acknowledges that due to global warming and the political situation, Israel will experience more fires in the future. It is for this reason, he says, that KKL-JNF introduced its early fire detection system 4 years ago, which consists of drones and masts equipped with advanced cameras, including tactical and thermal cameras, in mobile KKL-JNF stations around Israel. Then, a year ago, KKL-JNF introduced its first professional Command-and-Control Center, which provides real-time data on the rate of spread, wind directions, and changing wind directions, and allows KKL-JNF staff to manage a fire event as it unfolds.

“From here we can oversee the entire operation for managing a fire; forces, logistics, operational needs vis-a-vis our own forces and those of the Fire and Rescue Services,” says Zaretzki, gesturing towards the seemingly humble prefab room filled with monitors of all shapes and sizes. “The Command-and-Control Center allows us to control a very large area, thanks to all of our unique maps, including one that maps fire danger so that we know what resources to invest in a given area – for example, if a fire was to break out in Biriya Forest, the highest level of danger, I know right away to galvanize the firefighting pilots – and another one that maps the land characteristics, which include roads, communities, the placement of fire hydrants and the presence of a fire station.”

A few meters away from the CCC is a vehicle bearing a 10-meter-high pole, or toren, with a strong night vision camera attached, as well as a couple of drones, known as tinshemet – Hebrew for “Barn owl”, no doubt due to its ability to feed excellent birds-eye views of terrain in all sorts of conditions directly to the CCC. The system allows Zaretzky’s team to locate and monitor fire events in forests – even something as minor as a lit cigarette – from tens of kilometers away and send data points that direct the firefighters in real time. “We can even broadcast backwards to see how the entire event unfolds so that we can make the most efficient decisions,” Zaretzky says proudly. “We are the only organization in Israel today with the capacity to quickly determine a given line of fire and with that to begin working.” The CCC itself is entirely independent and has its own generator for emergencies.

It’s not all about technology, however. Since we don’t know what will happen tomorrow, KKL-JNF takes active measures to prevent the next fire in the next forest. Shali Ben Yishai points out that Biriya Forest, for example, expands over 2,200 hectares; of these 420 hectares have been burnt, “just so you understand how much potential remains for it to burn further. That is why we are currently bringing in machinery to fix access routes and create fire lines in Biriya Forest.”

According to Ben-Yishai’s cautious estimate, about 35% of the area burnt here will take a long time to recover; the tall trees, be they coniferous or broadleaf species, take decades or even a jubilee to attain the heights that we are accustomed to seeing.

The return of the undergrowth is slightly more complicated, since it depends on the health of the top ground layer of soil, which is the most significant in terms of organic materials and minerals. While a single fire doesn’t significantly alter the upper ground layer, a recurring fire, or a single fire of high intensity – 1500-2000 degrees Celsius – essentially bakes the upper layer, as in a kiln. At that level of ground damage, it will take two years for the vegetation to grow back. Where the soil remains unaffected, the undergrowth is likely to grow back within a year.

“There is also the issue of recurring fires, in places that were previously restored, whose restoration of soil and growth took a lot of time and effort,” says Ben Yishai, in reference to the forested area rehabilitated after the 2nd Lebanon War, which has seen fire once again. “This necessitates us to think deeply about how we want to restore such areas – do we rely solely on natural renewal? Are there certain places where we should intervene?”

KKL-JNF’s forestry research unit is dealing with exactly these questions, and many more, in anticipation of the years ahead. “The situation is so fluid here; we could completely rehabilitate the area as needed and then in another 10 years another war could break out and cause it to burn again,” Ben Yishai points out. “Therefore, the restoration needs to be considered, and correct, with regards to ecology and nature, so that it will know to revive itself if the situation arises.”